Only one civil servant monitors politicians’ assets

Klara Škrinjar, Matej Zwitter, Žana Erznožnik, Maja Čakarić, Samo Demšar

—

In Slovenia, no one except the Commission for the Prevention of Corruption knows what assets high-ranking officials own. They cannot judge whether they are gaining illicitly from holding public office. This is why Oštro has decided to turn the light on for the public and track politicians' assets in the Asset Detector.

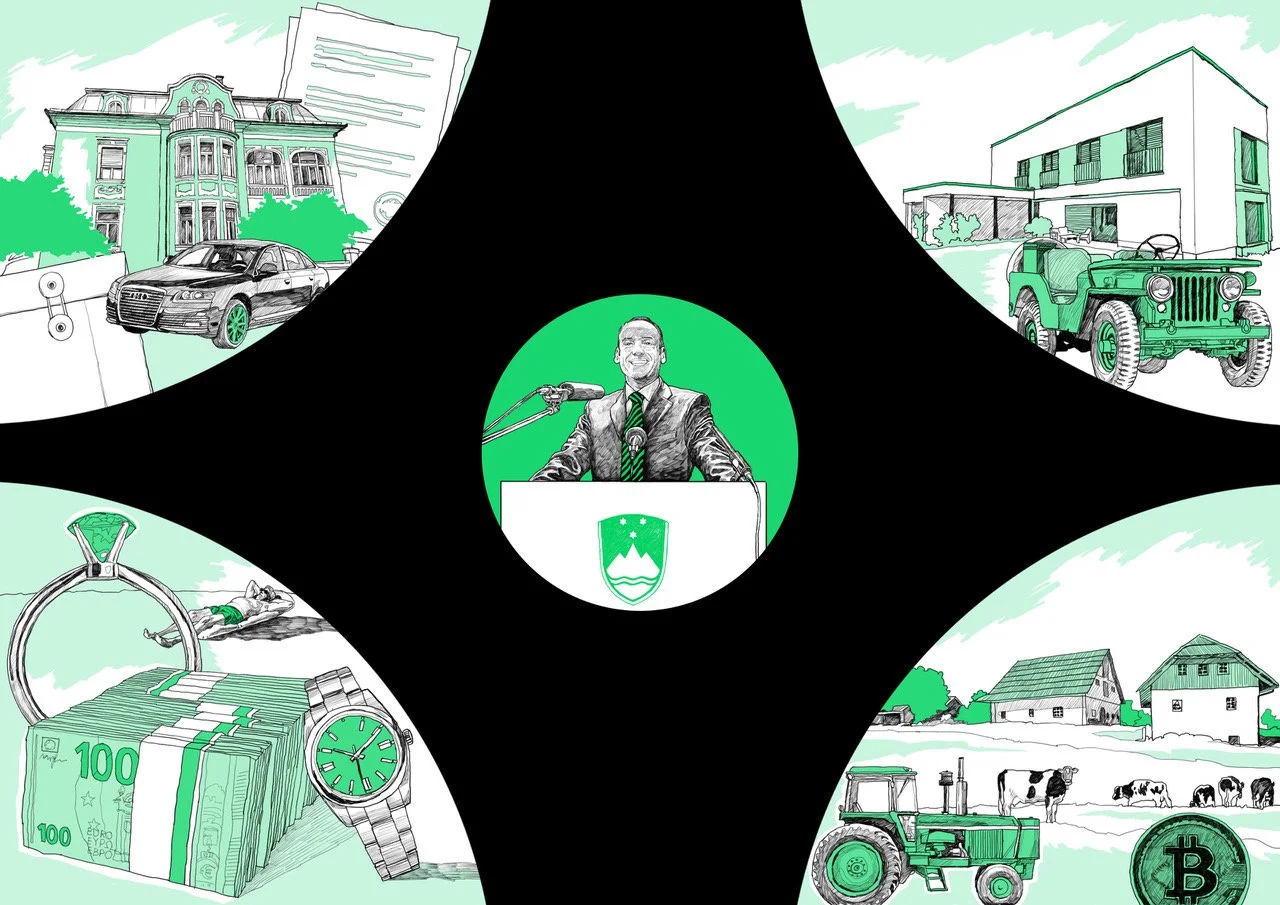

Illustration: Istvan David

Key findings:

According to the integrity and prevention of corruption act, only data on changes in officials' assets is publicly available.

The published data is scarce and, in some places, even incomplete. Currently, only 1 Commission for the Prevention of Corruption (KPK) employee oversees the assets of approximately 22,000 persons obligated to report.

Out of the 21 government members, initially, only Minister of Internal Affairs Boštjan Poklukar provided a copy of his asset declaration. After follow-up requests three more ministers submitted their copies.

Four ministers shared copies of their income tax returns.

Six ministries did not provide data on companies connected to them to KPK to be included on the list of companies with restrictions in doing business with state bodies.

At least four ministries eventually provided this to KPK after receiving inquiries from Oštro. Among other reasons, they attributed the delay to their ignorance and negligence.

“The Minister has reported all data on his assets to the Commission for the Prevention of Corruption in accordance with the law." This was the most frequent response by ministers to Oštro's request to provide a copy of their asset declaration filed with the Commission, and their most recent income tax return.

Of the 21 government cabinet members, only Interior Minister Boštjan Poklukar initially shared the declaration with Oštro, and three others responded to the reporters’ follow-up requests. Four provided a copy of the income tax return, a few others replied to Oštro's questionnaire on asset data, while some only sent a copy of the declaration.

In recent years, some candidates for political office have voluntarily disclosed their assets. In the last presidential elections, the incumbent President Nataša Pirc Musar and her opponent in the run-off Anže Logar did so, as did Marta Kos before she withdrew from the race. Levica MPs also published their declarations on the party's website in the last parliamentary term.

Access to data on assets of those holding the highest positions in the state can significantly contribute to transparency of public office, as well as to building trust in the conduct of public officials.

Under the integrity and prevention of corruption act, only data on changes in assets during an official’s mandate is public. However, the published data is scarce, some of it incomplete, and the declared assets of some 22,000 officials are currently under the watchful eye of just one employee of the Commission for the Prevention of Corruption. One other employee is currently absent from work.

The Ministry of Justice believes that the limited disclosure of politicians' assets is not in line with the purpose of the law, which is to strengthen transparency and public trust in public office holders. This is why Oštro has taken up the task of creating a database of officials' assets.

In the investigation which began in September 2022, it emerged that as many as six ministries did not provide the Commission with data on companies connected to ministers that the Commission should have placed on the list of companies subject to restrictions in their dealings with the state. At least four ministries did so after receiving questions from Oštro.

The Asset Detector is an open-access database where Oštro’s reporters publish data on assets of Slovenian political officials. The journalists obtained the data from public registers and other publicly available sources. The first publication concerns the assets of ministers; others will follow.

"Time and time again, internal oversight of asset declarations has proven insufficient," Helen Darbishire, Executive Director of Access Info Europe, a Spanish NGO advocating for the freedom of information, told Oštro. Public access to asset declarations is essential as a control against illicit enrichment, she said.

In addition, she says, the public is entitled to know whether an official has assets independent of the office they hold or whether they have other sources of income that could influence their decision-making. At the same time, public oversight is an incentive to be honest and complete in the initial declaration and is a disincentive against illegal enrichment.

The data format is important as well. As the Director of Access Info Europe says, such data should be published in open data formats with permission for re-use. "This is essential for investigative journalists, civil society but also for members of the public who need to know about the politicians they elect and the public officials who take decisions which affect citizens’ daily lives.”

The Commission for the Prevention of Corruption began publishing limited information on changes in officials' assets in February last year, although the law on integrity and prevention of corruption has provided the legal basis for this since 2010. The information that the public can access is stripped of almost all the details that the public needs in order to exert its rightful oversight and assess whether changes in an individual official's assets are in line with their official income.

Maruša Babnik, secretary general of Transparency International Slovenia, agrees that the current method of publishing data on changes in the assets of public officials is insufficient. She also points out that the data is not published in a machine-readable form, which makes analysis even more difficult.

"The published dataset raises more questions for the user than it answers. For example, it does not indicate the type of acquisition or disposal of property, which means it does not distinguish between a purchase, a gift and an inheritance. And this is despite the fact that the form for reporting changes in assets should, by law, also include the possibility to indicate the reason for the increase or decrease in assets," Babnik told Oštro.

Screenshot of public disclosure report, showing changes in the assets of public officials. Source: The Commission for the Prevention of Corruption

The grip of privacy protection

Drago Kos, who headed the Commission for the Prevention of Corruption from its inception in 2004 until 2010, pointed out that public disclosure of all information on the assets of officials, except for property identification data, is a well established standard worldwide. "The general data protection regulation and the practice resulting from it have done enormous damage to the fight against corruption and for transparency. This rigid approach, which is also practiced by the Slovenian Information Commissioner, has caused considerable damage to the fight against corruption."

Boris Štefanec, who headed the Commission between 2014 and 2020, likewise believes that all assets held by officials should be made public, not just the changes, mainly so that the public, taxpayers and journalists can scrutinize it during the officials’ term in office. He believes that "anyone who chooses to be a top official should agree to make their assets public".

"I don't see what would be wrong with that. If I was the prime minister, for example, I shouldn't be earning anything else than a salary anyway." Štefanec believes that officials should also disclose assets of family members, at least those of their spouses and children.

“Due to the large number of officials obliged to report their assets, the competent authorities do not have the capacity to control them and officials are naturally aspiring to keep reporting to a minimum.”

Kos acknowledged to Oštro that he himself was initially against making asset data public. "But then I saw in other countries that public disclosure is important so that everyone interested can see what officials have." In addition, journalists as well as the general public can contribute to completing the information on assets, as the competent authorities do not have the capacity to control them and officials are “naturally aspiring to keep reporting to a minimum.”

"In Ukraine, for example, it was through a public asset declaration and with the help of journalists that the former president was found to own large villas in Spain. Without the public declaration, this would not have been possible, because the journalists and the public would not have known what the president had declared, and the commission would not have known what else the president owned, because they do not comb through all countries of the world. That is why it is important that the public can help in obtaining complete information on the assets of officials," Kos is convinced.

Darbishire also emphasized that the range of information to be reported should be broad enough, as officials do not only profit directly from finances, they may also receive luxury items, holidays and such as a gift from someone who is bribing them.

PM keeping it brief

The data presented on the Asset Detector platform is not complete or comprehensive since only public data sources were available to Oštro, and in the month prior to the platform launch also data sent by members of the government at the journalists’ request. The Asset Detector is thus the first example of a systematic public disclosure of Slovenian officials’ assets to date.

Before going public, the journalists informed all members of the government in detail on the data they had obtained about their assets.

Interior Minister Poklukar was the first to send Oštro his asset declaration form, and subsequently answered additional questions. Culture Minister Asta Vrečko, Agriculture Minister Irena Šinko and Environment, Climate and Energy Minister Bojan Kumer also sent copies of their latest asset declarations.

View over Kromberk, the town, where prime minister owns some land plots, Photo: Oštro

Prime Minister Robert Golob provided only brief descriptions of his assets. His office said that he has bank savings and investments in mutual funds. He owns a car, an orchard with a small outbuilding, an olive grove, and some land plots around Kromberk. He has no outstanding loans.

Land registry records show that three of the four land plots above Kromberk that Oštro was able to identify are encumbered with a mortgage from 2014 worth €73,000.

At the time of publication, the prime minister’s office had not yet replied to a follow-up question on whether the mortgage had been paid off. There are a few more plots of land in the area that are co-owned by the prime minister.

A house on the seaside

"I will do what I announced, I will no longer be a shareholder." This is how Economy Minister Matjaž Han answered a question by N1 last year, two days before his appointment, about whether he was committed not to exploit the ministerial post for himself or for his company M & M International.

Han started this retail, manufacturing and service company with his late father in 1992, before entering politics. He was its director until 2009; during this time he was, among other things, the mayor of Radeče and a member of parliament. The company has so far generated just over €198,000 of revenue from public funds.

As promised before he took office, he ceased being an owner in August 2022, when he signed over his 50% share in the company to his wife. The notarial deed shows that she paid nothing for the stake worth just over €146,000.

According to the register of beneficial owners, Han is the sole beneficial owner of M & M International, which also does business with the para-state energy group Petrol. As he told Oštro, he asked the Commission for the Prevention of Corruption about whether this business relationship may be problematic and "they told him that there was nothing controversial", even when he took over the current ministry.

The Commission told Oštro that they had not received the minister's inquiry. Oštro brought this to Han's attention, whereupon he clarified that he had not asked about this officially and in writing, but informally on the phone, when he was asking for advice prior to declaring his assets.

Several media, among them 24ur.com, have reported that Han and his family have been holidaying on Pag Island in Croatia for many years. According to the Croatian land registry, he and his wife have owned a holiday home in Mandre since end of September 2018.

According to the asset change declaration sent by Han to Oštro, the house has a liveable area of 62 square meters. Separately, Han explained that the house has 146 square meters of adjoining land and about 582 square meters of undevelopable land. Han was a member of parliament at the time of purchase.

The sales and purchase agreement obtained by Oštro with the help of Oštro's sister center in Zagreb shows that the Hans paid €165,000 for the house, which, according to Google Maps, sits less than 150 meters from the sea. Han explained that he and his wife had taken out a loan of €40,000 each and financed the rest with proceeds from the sale of investment fund assets.

Sanja Ajanović Hovnik. Photo: Nebojša Tejić/STA

All in the family

Until last summer, Public Administration Minister Sanja Ajanović Hovnik was also the owner of a company. In August 2020, she founded Smart Center, a business consultancy which advises on digitalisation, sustainability and democratization of organizational processes, along with entrepreneurs Kaja Primorac and Alja Žorž.

According to Erar, the Commission for the Prevention of Corruption’s register of transactions between the public and private sectors, the company has so far generated just under €24,000 in revenue from the public sector.

Ajanović Hovnik was director and co-owner of Smart Center until mid-June 2022, when, two weeks after her appointment as minister, she donated her 50% stake to her mother, a retired nurse who reportedly has no experience in business consultancy. Until recently, the company had not entered its beneficial owners in the register of beneficial owners despite being required to do so by the anti-money laundering law.

On 8 May, Oštro asked Ajanović Hovnik about the suspicion that she is the straw owner of Smart Center and about the company’s non-registration in the Register of Beneficial Owners.

A change took place the next day, on 9 May, when Kaja Primorac, 50% owner of Smart Center, was registered as the beneficial owner of between 25 and 50 per cent of the company. The third co-founder, Alja Žorž, had already left the company in April 2021. It is therefore still unclear who is the beneficial owner of the other half of Smart Center.

Under the provisions of the anti-money laundering law, changes in the ownership of a company of at least 25% must be entered in the Register of Beneficial Owners within eight days.

"A lack of transparency of ownership suggests the possibility of straw ownership," Transparency International Slovenia said. In their view, the case shows that "legislation on timely and full disclosure of beneficial ownership has not been complied with. If the owner is a family member of a high-ranking official, the company should also have been placed on the list of companies subject to restrictions in doing business with the state on the Erar portal."

Under the integrity and prevention of corruption act, when family members of ministry officials own a business the ministers must report this to the ministry within eight days, which in turn reports to the Commission for the Prevention of Corruption. The latter maintains a list of entities which are subject to restrictions in doing business with state bodies, which is a measure to protect public funds from spending that is motivated by private interests.

After receiving Oštro’s questions, the Commission found that the Public Administration Ministry had not reported Smart Center's ownership. They asked the ministry for clarification.

At least two more entities with links to minister Ajanović Hovnik – the sole trader Danilo Hovnik, her husband, and the Institute for Sustainable Mobility Maribor, which was co-founded by her mother – are also not on the list of companies subject to restrictions on doing business with the Public Administration Ministry.

Minister Ajanović Hovnik did not respond to Oštro's questions about her assets, the transfer of Smart Center to her mother and its beneficial ownership.

The ministry's Public Relations Office only repeated several times that the minister reports her assets to the Commission in accordance with the regulations. Just before publication, they clarified why companies related to the minister's family members were not included in the list of entities subject to restrictions on doing business with the state.

"It is true that the minister did not declare the business entities that are subject to restrictions when she took office, because at that time, with all her commitments, she did not pay attention to this, nor did anyone warn her about it. It was by all means a mistake which the minister acknowledges and for which she sincerely apologizes. She fulfilled her obligation to inform the Commission for the Prevention of Corruption of the business entities subject to restrictions as soon as it was brought to her attention."

She added that her husband's company and Smart Center did not do business with state administration bodies, and she was not aware of the operations of the Maribor Institute for Sustainable Mobility, but "to her knowledge it did not do business" with the public sector.

Prior to the launch of Asset Detector, the list of entities subject to restrictions on doing business with the state did not include companies, institutions or self-employed persons to Minister Poklukar, Health Minister Danijel Bešič Loredan, Foreign Minister Tanja Fajon, Justice Minister Dominika Švarc Pipan and Digital Transformation Minister Emilija Stojmenova Duh.

Some of them explained to Oštro that this was due to ignorance and negligence – they assured reporters that the irregularities were being corrected. However, the Commission for the Prevention of Corruption announced that it would check the individual cases Oštro enquired about.

The Šiška neighborhood where Minister Bojan Kumer owns an apartment. Photo: Oštro

No irregularities found on Kumer’s apartment

In the autumn 2016, electricity distributor Elektro Ljubljana sold an apartment on the second floor of an apartment building in Ljubljana's Šiška neighborhood to Bojan Kumer, at the time the director of a subsidiary Elektro Energija, who is today the environment minister. Just under six years later, shortly before last year's general election, the company fired three employees and filed a criminal complaint against Andrej Ribič, the CEO at the time, for alleged abuse of office, and Martina Pohar from the company’s legal department for complicity in the crime.

Among other things, they were accused of selling the apartment to Kumer below market price and not securing a supervisory board clearance for the sale, the company told Oštro.

In an interview for public broadcaster RTV Slovenija last year, Kumer said the low price was due to the poor condition of the apartment: "It was dilapidated, uninhabitable, and it is the normal right of a lessee to secure his pre-emptive right to purchase, if he starts investing his euros in an apartment." Today, he rents it.

He explained to Oštro that the police had questioned him as a person who could have useful information. "The agreement was not fictitious, as evidenced by the paid rent. The purchase price was not lower than the market price at the time, as confirmed by the sworn appraiser."

The head of the Ljubljana Public Prosecutor's Office, Katarina Bergant, told Oštro in May that the charges in the case were dropped on 21 April.

"It was established in the proceedings that the apartment was sold at a reasonable price, which was determined by a sworn appraiser, and that the appraiser performed her work professionally," Elektro Ljubljana said about the case, adding that a supervisory board's clearance was not required for the transaction.

(Un)public oversight

Transparency International Slovenia’s Maruša Babnik pointed out that the Commission for the Prevention of Corruption is allowed by law to publish its findings on the correctness, completeness and timeliness of the reporting by officials on changes of their assets. The currently published data does not show that "the Commission has carried out a review of the financial activities of officials and whether it has detected any irregularities in the process".

The Commission adopted its decision on the launch of oversight of the correctness of reporting by current officials of the National Assembly, the government and ministries in August last year. The Commission's senate adopted its report on 10 January, but it was not published online. Oštro obtained an electronic copy under a freedom of information request.

The Commission found that 41 out of 62 members of the government and 48 out of 91 National Assembly officials covered by its review had not properly fulfilled their legal obligations when declaring their assets.

The most significant errors were detected in the reporting of real estate, real estate rights and other property rights, cash at banks, savings banks and savings and credit institutions, and debts, liabilities or guarantees assumed and loans granted.

The Commission’s president Robert Šumi told Oštro that the findings of the review resulted in small offenses proceedings, but the details thereof will not be disclosed until they are final. In general, he is disappointed by the insensitivity of political officials to issues related to their own integrity.

As he explained, candidates had been informed of the obligations to declare assets, the restrictions and incompatibilities of public office before last year's general and local elections. After the elections, they were also sent a link to an information package which he said was easily accessible online. They were also informed through other communication channels about all their obligations under the integrity and prevention of corruption act, including on asset reporting.

"This is, plain and simple, wilful ignorance rather than passivity", he said about the timeliness and accuracy of officials' reporting. "There needs to be a rethink about where we are."

A European rainbow of reporting standards

EU countries have introduced a plethora of practices for declaring assets and publishing officials’ asset declarations. In some countries, this data is not publicly available, in others it is available only on demand while most publish it online with varying degrees of detail.

However, no country has a system in place to control politicians' assets to the extent that it could be considered a model for others, Helen Darbishire of AccessInfo Europe told Oštro. She cited France and, since recently, Romania as countries that have achieved a certain level of transparency in this are.

With the help of colleagues from other EU countries, Oštro has compiled a review of the publication of officials' assets and classified them into six categories of transparency.

The top category includes countries that publish at least specific information on real estate, vehicles, stakes in companies and securities, and cash held by officials. This includes Croatia, where, in addition to the assets of officials, information on the assets of their spouses and children is made public. Eight countries in Eastern and South Europe have a comparatively high standard of public disclosure, while in Western Europe France stands out for transparency.

In Slovakia, Ireland and Latvia, detailed information is made public only on certain types of assets, and in Denmark and Luxembourg only on equity stakes in companies. Six countries, including Slovenia, publish incomplete data or aggregated values by asset type. Portugal, Sweden and the Czech Republic make asset reports available only on demand, and in four countries in Central and Western Europe the data is not publicly available.

In Slovenia’s neighborhood, databases such as the Asset Detector have been launched by journalists or non-governmental organizations in Croatia (Mozaik veza), Serbia (Baza imovine političara) and Bosnia and Herzegovina (Baza imovine političara).

"Setting up the database was a big challenge, especially because we were practically pioneers in this field in Serbia," Bojana Jovanović, deputy editor-in-chief of Krik, the Serbian Centre for Investigative Journalism, told Oštro. "We were doing something that no one had ever done before."

One of the things that prompted Krik to launch the project in 2016 was Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić’s asset declaration. "Judging by it, he was one of the poorest officials in the world, owning only a studio apartment in Belgrade," Jovanović said. In Serbia, officials are required to declare their assets and income to the anti-corruption agency, as well as that of their spouses and children.

Krik subsequently discovered that Vučić owned one property in the Serbian capital and members of his family owned six, which at the time were worth a total of more than €1.1 million. Two of the apartments were bought from the state in the 1990s on favorable terms, Jovanović explained. "Another interesting fact is that Vučić's studio apartment is right next to his wife's apartment, which is about 100 square meters."

In 2017, the project was awarded the Global Data Journalism Award in the Open Data category by GIJN, the Global Investigative Journalism Network.

The publication of asset data of ministers and the analysis is the first phase of Oštro’ project which is simultaneously implemented by sister investigative journalism centers in Slovenia and Croatia. Data on other groups of officials is coming up in Fall while all data will be updated periodically.

The following reporters helped Oštro collect information on publicity of asset declarations in other EU countries: Thomas Hoisl (Austria), Kristof Clerix (Belgium), Atanas Tchobanov (Bulgaria), Stelios Orphanides (Greece, Cyprus), Pavla Holcová (Czech Republic), Staffan Dahllöf (Denmark, Sweden), Minna Knus-Galán (Finland), Stéphane Horel and Léa Sanchez (France), Harald Schumann (Germany), Lois Kapila (Ireland), Giulio Rubino (Italy), Sanita Jemberga (Latvia), Šarunas Černiauskas (Lithuania), Luc Caregari (Luxembourg), Jacob Borg (Malta), Lise Witteman (Netherlands), Sofia Rodrigues (Portugal), Attila Biro (Romania), Lukáš Diko (Slovakia) in Marcos Garcia Rey (Spain). Thank you!