Inside scandal-rocked Danske Estonia and the shell-company ‘factories’ that served it

Simon Bowers, Karrie Kehoe and Holger Roonemaa, ICIJ

–

The FinCEN Files reveal how a handful of secretive agencies mass-produce U.K. shell companies owned by criminals and launderers from former Soviet states.

Illustration: ICIJ, BuzzFeed News

The Estonian banker was frantic: A whistleblower inside the bank suspected nine anonymous companies — all registered in the United Kingdom — of serious financial crimes and was threatening to go to authorities.

“The whistleblower demands ALL OF THESE CLIENTS … ACCOUNTS be closed in 48 HOURS,” Aivar Rehe, the head of the Estonian branch of Denmark’s Danske Bank, wrote in emailed instructions to his staff.

In that moment, in 2014, one of the largest money laundering scandals in history was starting to unravel in the scandal’s unlikely banking hub of Tallinn, Estonia, capital of one of the Baltic States, three little countries tucked between Russia and the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe.

At the heart of the scandal: hundreds of mysterious U.K.-registered companies that had accounts at the bank but no apparent business operations and no publicly visible owners.

Five years after writing that desperate email, Rehe was dead — found in his family’s garden in a suburb of Tallinn. The 56-year-old banker had used an extension cord to hang himself from a tree. Later, the cord snapped, and his body fell into a ditch and went unnoticed for two days.

By then, Danske Bank Estonia was consumed in a $230 billion money laundering scandal.

Newly leaked Estonian police files, including internal paperwork taken from Danske Estonia, reveal the extraordinary steps a tiny division of the Tallinn bank took to serve a shadowy, and highly lucrative, clientele largely from Russia and from former Soviet republics and satellites in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. The documents show that many bank accounts were held in the name of U.K. vehicles, known as “limited liability partnerships,” or LLPs, and “limited partnerships,” LPs, which had no purpose other than to hide the identity of who really owned the money.

An investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists found that thousands of LLPs and LPs that owned accounts at Danske Bank and elsewhere had been mass produced by only a handful of secretive agencies that registered them at government offices in Cardiff, Wales, and other U.K. locations.

Almost all these agencies, ICIJ found, were run by individuals with personal ties to the Baltic region, often with links to Baltic banks, including Danske Estonia; some agencies helped LLPs and LPs open Baltic bank accounts for their secret clients.

The Estonian police records, obtained by ICIJ’s Italian partner, L’Espresso, reveal that the Danske Estonia bankers — required by law to vet their customers to prevent money laundering — instead ran a secret company on the side that helped set up U.K. LLPs and LPs that were designed to conceal the identity of bank clients.

Aivar Rehe’s 2014 email to colleagues, flagging the whistleblower demands.

Rehe’s frantic email was about nine LLPs and LPs, but in fact the bank was overrun with this brand of U.K. shell company, which had become a vehicle of choice for international criminals and corrupt officials seeking to hide ill-gotten gains.

The Estonian police documents supplement another, larger cache of documents known as the FinCEN Files: top-secret reports that banks suspecting money laundering are required to send to a U.S. Treasury Department agency known as the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, or FinCEN.

The Treasury documents, obtained by BuzzFeed News and shared with ICIJ and 108 media partners, include more than 2,100 suspicious activity reports filed by major banks that control access to U.S. dollars and process transactions for smaller banks like Danske Estonia. The reports are known in banking circles as SARs.

An ICIJ data analysis found that the FinCEN Files contained a startlingly large number — 3,267 among just more than 2,600 leaked files — of U.K.-registered LLPs and LPs.

SARs in the FinCEN Files show the New York operations of Deutsche Bank and other global banks playing a critical role at the center of what is a money laundering conveyor belt. ICIJ found the banks overlooked obvious money laundering signs and routinely waved through U.K. LLP and LP transactions from accounts at Danske Estonia and many other Baltic banks. The processing of international payments in New York is a critical step in concealing the money’s true origins.

Together, the FinCEN records, the Estonian police documents, and ICIJ’s data analysis provide a comprehensive view of the sprawling money laundering industry: from the creation of U.K. LLP/LPs in Cardiff, Wales, to banking them at Danske Estonia in Tallinn, to finally moving their dollar transactions in Lower Manhattan.

The importance of being a UK LLP or LP

U.K. business partnerships date back centuries. But they only became popular with money launderers in the early 2000s after the United States and some banks tightened rules on certain kinds of U.S. corporate entities and on shell companies in notorious secrecy jurisdictions such as the Cayman Islands, the Seychelles or the Isle of Man.

U.K. registration and the LLP and LP forms — commonly used by British law firms, accounting firms and other businesses — offer a patina of legitimacy that offshore havens can’t. As a result, the number of the U.K. LLPs and LPs has skyrocketed, from fewer than 20,000 in 2004 to more than 100,000 in 2017. (LPs, many established under Scottish law, have fewer disclosure requirements, but are otherwise similar to LLPs.)

Many are set up through formation agencies, which for a fee, register LLPs and LPs online at Companies House and provide other services to keep the true owners anonymous.

Despite their bland name, the impact of anonymous U.K. LLP and LPs can be anything but bland; they’ve been used as cover for people tied to serious financial crime — and worse.

Among these: Aierken Saimaiti, one of the most successful money launderers in Kyrgyzstan, made extensive use of LLPs with bank accounts in Latvia. Kyrgyz authorities believe that he and associates channeled close to $1 billion in dirty funds out of the country between 2011 and 2016. He was shot dead outside a cafe in Istanbul in November 2019.

And there is Altaf Khanani, a U.S.-sanctioned global money launderer said to have moved illicit money for Australian biker gangs, Mexican drug cartels, even al-Qaida. The FinCEN Files and other leaked documents show one of his key laundering fronts was involved in transactions with LPs separately linked to Russian money laundering. In 2016, he was sentenced to just 68 months jail as part of a plea agreement. He was released in July.

And there’s Lazar Shaybazian, an Uzbek associate of violent Russian mafia boss Vladislav “Blondie” Leontyev, who controlled a Dubai-based jewelry firm which received payments from an LLP banking in the Baltic region. Shaybazian was sanctioned by the United States in 2012 for his ties to Leontyev, a senior figure in a group referred to as the “Brothers’ Circle,” notorious for drug trafficking and violence. And these are just the beginning.

The rise and misuse of anonymous U.K. LLPs and LPs attracted critics, and in 2016, the government moved to require most British companies to disclose individuals with more than 25% control. While the rules apply to all LLPs and to some LPs, the law contains no verification or enforcement mechanism, and many don’t provide ownership information.

“If you’re intent on masking the ultimate ownership and control of a company, these rules do nothing to stop that happening,” said Graham Barrow, an expert who has advised several global banks on combating money laundering.

Two days before ICIJ and its media partners started publishing FinCEN Files investigations, the U.K. government announced new reforms it said would help weed out money laundering shell companies. They promised verification checks would be made on the identity of directors, owners and formation agents.

The FinCEN Files, a fraction of all SARs filed by global banks, are a jumble of narrative reports of varying quality that reveal the private concerns of global bank money-laundering compliance departments about certain transactions. Some come with attached spreadsheets of raw transaction data. Many have no spreadsheet attached. And many spreadsheets — filled with interested parties’ names, bank names, figures, and dates — came unattached to any narrative to explain them.

According to BuzzFeed News, some of the records were gathered as part of U.S. congressional committee investigations into Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election while others were gathered following requests to FinCEN from law enforcement agencies.

Matching U.K. shell company names and other information in the FinCEN Files against Companies House records, ICIJ identified 3,267 LLPs and LPs as holders of bank accounts — many at Baltic banks — involved in transactions flagged as suspicious.

As it turns out, many of the LLPs and LPs had features in common — the same mailbox addresses, signatures, and so-called nominee owners, normally other shell companies in far away tax havens — pointing to a handful of actors, each of them formation agencies, creating many entities.

An ICIJ data analysis found that more than half of the U.K. LLPs and LPs in the FinCEN Files — 1,656 — were all created by the same four agencies. Nine agencies each created more than 100 U.K. entities mentioned in the leaked SARs; one was responsible for 646. Further reporting discovered that many of these agencies were run by individuals living in the Baltics or Baltic nationals living in the U.K.

A U.K. LLP or LP can appear in the FinCEN Files for a number of reasons. Some had been flagged based on bank compliances officers’ cursory investigations of transactions that they believed showed signs of money laundering. Some appear in spreadsheets without the narrative attached.

And some played a clear-cut role in money laundering, fraud, grand corruption and other wrongdoing.

U.K. law requires LLPs to file annual financial statements with Companies House.

ICIJ’s investigation found the signature of a Belgium-based dentist on Companies House financial statements of nine LLPs that understated their revenues by more than $4.1 billion. The dentist says his signature had been forged and that he had never heard of LLPs.

The data show that while U.K. LLPs and LPs in the FinCEN Files made extensive use of Danske Estonia, they also used an array of other, mostly Baltic, banks, including scandal-ridden ABLV Bank, Trasta Komercbanka in Latvia and Stockholm-based Swedbank’s Estonian branch.

Formation agencies’ Baltic ties

For some formation agencies, creating shell companies is a volume business.

One of the busier agencies found in ICIJ’s analysis is CMC, a network of companies in the Seychelles, the U.K. and Latvia, operated by Dmitrijs Krasko, a Russian-speaking entrepreneur who had started in the business after a spell as an intern at Latvia’s ABLV Bank. Some 112 U.K. companies established by Krasko and his team are named in the FinCEN Files. Krasko’s signature appears on hundreds of incorporation documents and annual financial statements for U.K. LLPs and LPs that claim to operate in industries as diverse as electronic equipment, coal purchasing, leather goods and freight shipping.

ICIJ partner Re:Baltica, based in Riga, Latvia’s capital city, approached Krasko in June on the lush Ozo golf course on Riga’s outskirts, where he was playing in a tournament popular with senior bankers. Wheeling a golf bag along a gravel path near the course, Krasko defended the bulk production of anonymous U.K. LLPs, LPs and other companies and said some of his competitors create many more than CMC does.

“You want to sell companies,” Krasko explained. “You’re looking for customers. That’s how it should work; otherwise it’s not profitable.”

Krasko has signed annual financial statements for hundreds of U.K. LLPs, but he said, “There is no possibility that we can be 100 percent sure what this company is actually doing.”

He added: “But we have our due diligence policy and our [anti-money-laundering] policy. And we collect the information which, to our knowledge, is correct.”

On its website, Krasko’s agency also advertises, in Russian, that CMC helps customers open bank accounts at “leading Baltic, European and Offshore banks” for the U.K. LLPs, LPs and other firms it creates. And the actual customer needn’t even show up at the bank.

“Our company has concluded agency agreements with a number of banks, which allows us to carry out client identification,” the website says. “In this case, the client only needs to meet with us to open a bank account.”

In answers to written questions from ICIJ, Krasko said he was in the process of shutting down his formation agency, and that CMC had never helped a customer open a bank account, at ABLV or elsewhere. He said he carries out anti-money laundering checks in accordance with U.K. regulation and he only signs LLP financial statements to ensure the paperwork is promptly filed. “It might take months to deliver a letter from any CIS country to U.K.,” he said. “Not to mention that letters could have been easily lost on its way to Companies House.”

Krasko says there is no risk to him if the financial statements are false because he insists on an indemnification agreement before signing them.

Much paperwork, no place of business

Formation agencies are often loose, low-profile networks of companies operating across many countries. The agencies typically offer a full suite of secrecy-protection services: paperwork preparation, an official U.K. address — sometimes just a post office box shared by hundreds of LLP and LP shell companies — and functionaries paid to sign the paperwork.

In filling out Companies House forms, a formation agency usually lists the publicly declared “owners” as other shell companies — invariably registered in secrecy havens such as Belize, Panama or the Seychelle Islands — that are owned by the formation agency itself. The paid functionaries, essentially straw men or women, usually sign as a representative of one of the anonymous shell company owners.

As a final maneuver, the formation agency writes a private power-of-attorney letter secretly transferring full control of the new company to its true owner, who, in exchange, often indemnifies the shell company owners, shielding the formation agency from any legal threat.

U.K. shell companies usually have no greater connection to Britain than a mailing address, often a post office box at a mail-forwarding company. An ICIJ analysis found that at least 393 LLPs and LPs in the FinCEN Files have been registered to nine Mail Boxes Etc. stores, including in London’s Mayfair district, Dundee, Scotland, and Belfast, Northern Ireland. Mail Boxes Etc., based in Milan, Italy, is a provider of post office boxes and other services.

A Mail Boxes Etc shopfront in Glasgow. Image: via Google Maps

Hilux Services LP, one of several U.K. shell companies linked in a scheme to launder $2.9 billion from Azerbaijan, listed its address as Suite 1135, 111 West George Street, Glasgow, Scotland. Leaked paperwork shows that Hilux Services’ partners even said they held a meeting there.

In fact, the company address is a Mail Boxes Etc. store. “It’s really just a mailbox,” a salesperson there told ICIJ. “There are no meeting rooms. It’s just an inexpensive way to have a city-center address if you’ve got a company. Meeting rooms we don’t have, no.”

A private home in Leicester, in England’s Midlands, was the registered address of 36 shell companies that had accounts at Danske Estonia, 11 mentioned in the FinCEN Files and two companies named in a leaked U.S. Treasury intelligence report as being involved in a Russian money laundering scandal known as the mirror trades.

The occupant of the house is a Latvian house cleaner and beautician named Dace Streipa. In a phone interview with ICIJ, she said she knows nothing about shell companies.

“Many, many letters come to this house, but I always hand [them] back because it’s a normal family house, nothing else,” said Streipa, who has lived at the address for nine years. “I am a single mum. I’m only with kids, and I’m working cleaning houses, and that’s it.”

The Canterbury-Latvia connection

One busy agency, ComForm Solutions, with operations in the U.K. and Riga, is run by a British-based Latvian, Kirils Pestuns, according to U.K. and Latvian corporate records.

ComForm created and maintained 380 U.K. LLPs and LPs mentioned in FinCEN Files suspicious activity reports, according to an ICIJ analysis.

Pestuns, 36 years old, recruited James Dickins and Daniel O’Donoghue, former teammates of his on the rugby squad at the historic English boarding school King’s School, Canterbury. His two old schoolmates signed documents for hundreds of U.K. LLPs and LPs set up by ComForm.

In a telephone interview, Pestuns told ICIJ that the two former schoolmates signed the paperwork believing it to be correct “to the best of their knowledge.” However, he added: “We’re not banks, you realize that? So, we don’t see [our customer’s] transactions. . . . We’re not their accountants.”

Pestuns regularly speaks at sales conferences and tours Eastern Europe and Russia extolling the benefits of U.K. LLPs and LPs. His website boasts that Comform can set up a U.K. shell company for less than $330, arranging an LLP in three days, an LP in eight.

Asked what benefit an anonymous U.K. shell company provides his customers, Pestuns said, “Well, I’m sure you know. Why would you need to hear it from me?”

He added: “You best ask the people who buy [them]…. I think you’ve got the wrong end of the stick: you’re assuming that just because people don’t want you to know what they’re doing, that it’s instantly seedy or bad.”

In a later written statement, Pestuns said: “At ComForm, we understand [the] high level of due diligence that is required from UK company formation agents when meeting their regulatory obligations. In fact, I have given talks on the importance of adhering to such regulations in a number of countries.”

In an email, O’Donoghue said he had nothing to add to Pestuns’ comments. Dickins couldn’t be reached.

The most active of all formation agencies, IOS — sometimes known as International Overseas Services, International Offshore Services or IOS Group — was initially run by former staffers of Latvia’s Parex Bank who teamed up with a veteran formation agent, Philip Burwell, now based in Ireland. The agency, which set up and maintained 646 LLPs and LPs featured in the FinCEN Files, was initially based in an office opposite Parex Bank’s headquarters in Riga. The bank failed, but by then, the formation agency had developed ties to other lenders throughout the Baltic region.

In interviews and emails with reporters from ICIJ and its partner The Irish Times, Burwell said he stopped setting up U.K. LLPs for the Latvian arm of IOS in 2011, though he continued to create other anonymous companies with people from the formation agency after that.

“I never saw anything like what happened when the Russian market took off. It really got out of hand,” he said of the booming demand for LLPs and LPs. “There were banks that were set up to cater for that market, for the specific needs of the Russians, who are a very secretive people, and the whole thing got out of hand. And that’s why I didn’t want to be involved that deeply anymore.”

He said: “I removed myself as far as I felt comfortable with.”

Burwell said Irish police — often at the behest of law enforcement agencies in other countries — had asked him questions many times about companies he set up with IOS.

“I accept that LLPs and LPs created by IOS, some of which were set up by my firm, have been mentioned in many ‘scandals’, a few of which have been proven to involve actual criminality,” he said. However, he added that he believed much of the money leaving Russia did not represent the proceeds of crime or corruption.

On its website, IOS says that in early 2017 companies involved in the “franchise” had decided to slowly stop working together under the IOS name.

However, Companies House records show those involved in IOS are still active, maintaining hundreds of U.K. LLP and LPs and creating new ones as recently as October last year.

Inside Danske Estonia: a secret formation agency

In 2010, Regina Marčenkienė, a Tallinn-based photographer, got a call from someone offering a job designing business cards, invoice forms and letterhead for Beta Consult Corp., a company registered in the Marshall Islands, a secrecy haven in the central Pacific Ocean.

She created templates documents and sent them off. For clarity, Marčenkienė entered her own name as dummy text on the invoice templates. The woman who had hired her, Anastassia Kidjajeva, seemed pleased with the result.

Marčenkienė didn’t know that Kidjajeva was linked to, and is now married to, Juri Kidjajev, head of the private and foreign banking division at Danske Estonia. Marčenkienė also didn’t know that Beta Consult was a shell-company-formation operation, a wholesaler of sorts, run secretly by Danske Estonia bankers. Beta Consult worked with formation agencies to create U.K. LLPs and LPs for Danske Estonia clients, records show.

Marčenkienė’s 2010 design job was finished in about a week. But her name would appear on a Beta Consult invoice to a Danske Estonia client dated 18 months later.

Her name, picked up from the dummy text, appeared on a $2,800 invoice listing a U.K. LLP, Solidstar Worldwide, as the client. She was listed as the salesperson. Solidstar was among dozens of companies that sent or received funds from a multi-billion dollar Azerbaijani laundering operation, first reported by ICIJ’s media partner the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP).

In an interview with ICIJ’s Estonian media partner Eesti Päevaleht, Marčenkienė said she didn’t know her name was on the Beta Consult invoice, and at least a few others, until she was told by Estonian police. She said she had nothing to do with this sale, or any other. “Why would they use my name without even asking me about it?” she said.

A secret invoicing system for UK LLPs and LPs

ICIJ has learned that the last digit of the invoice number issued by Beta Consult was part of a code that linked sales to individual Danske Estonia bankers. In the Solidstar case, the number 4 signified Jevgeni Agnevštšikov, a Danske Estonia account manager now a named suspect in the Estonian probe. The bank’s records show that Agnevštšikov also served as Solidstar’s account manager.

Nine other private and foreign banking department staffers, including the division manager, Kidjajev, had similar code numbers for Beta Consult invoices, according to one email in the leaked Estonian police files. The email’s subject line read: “Inv + kodirovka.” “Kodirovka” means “encoding” in Russian.

These and other details about Beta Consult appear in email exchanges, largely among Danske Estonia bankers, found in the documents leaked to L’Espresso.

The documents also show that Beta Consult had its own account at Danske Estonia and that other customers of the bank — often U.K. LLPs — made dozens of payments into it.

Kidjajev and several colleagues from the foreign banking division are now the focus of the Estonian criminal investigation.

“Knowledge isn’t power in this business. Knowledge is contamination, so, you make sure you don’t get contaminated.”

The Danske Bank whistleblower

Danske Bank’s Tallinn operation had been run for more than a decade by Rehe, the executive who would hang himself in 2019. The 500-employee outpost was exceptionally successful.

And Juri Kidjajev, who reported to Rehe, was the star. He oversaw little more than a dozen account managers serving only non-Estonian customers from Russia, Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Foreign customers generated profits of $52 million in 2013 — representing 99% of profits within Rehe’s Estonian branch — and a return on allocated capital of 402%.

A floor below Kidjajev’s private and foreign banking division was a small currency- and bond-trading team run by Howard Wilkinson, a British national. Wilkinson had nothing to do with Kidjajev’s powerhouse division — until one day a young account manager from another division asked for help finding information on a U.K. LLP account holder, Lantana Trade.

A quick online check of Companies House records revealed a startling fact: Lantana Trade’s financial statements bore no relation to the large sums flowing through its account in Tallinn. In fact, the records said Lantana Trade was supposed to be dormant.

“It was, on the face of it, suspicious,” Wilkinson recalled in an interview last year with Fraud, a fraud-examiners trade magazine. Submitting false financial statements to Companies House is a crime in the U.K.

Wilkinson’s colleagues assured him that it was an innocent error, but a year later, rumors about Lantana caused him to check again.The filing had been revised but again didn’t match the bank’s data.

In late December 2013, Wilkinson wrote an email to the home office in Copenhagen with a stark subject line:

“Whistleblowing disclosure — knowingly dealing with criminals in Estonia Branch”.

In a note that detailed Lantana Trade’s false financial filings, he wrote, “The bank may itself have committed a criminal offence.”

Receiving nothing more than a polite acknowledgement, he kept digging and found 15 more Danske Estonia customers that had filed false financial statements, prompting him to send off two more whistleblower emails.

He urged executives in Copenhagen to investigate all U.K. LLPs and LPs banking at Danske Estonia and to report to Estonian police those found to have submitted false financial reports.

By early 2014, Wilkinson’s complaints were reverberating through the bank. Leaked emails show that Rehe, the Danske Estonia branch chief, became increasingly frantic and fought to stay ahead of the blossoming investigations.

The branch closed 853 accounts in 2014, many of them belonging to U.K. LLPs and LPs, a later bank investigation reported. Internal emails show that, in April of that year, 12 days after Rehe’s panicked email, the bank abruptly terminated relations with 10 LLP and LP customers on his orders. One member of staff from Kidjajev’s department was furious, describing the move as “unacceptable and incomprehensible” and noting that some of these companies had been among Danske Estonia’s large customers. In vain, she argued there were no grounds for shutting the accounts without notice.

Rehe’s belated action wasn’t enough. Regulators from the Estonian Financial Services Authority inspected Rehe’s unit and found that it had systematically taken on customers whose activities were very obviously suspicious — and that the branch’s scrutiny of those customers and their transactions was “effectively not working.”

Rehe’s branch contested almost all the findings. Meanwhile, Danske Bank executives in Copenhagen quietly tried to sell its Baltic operations, without success. In October 2015, Deutsche Bank cut off the Estonian branch from its dollar clearing services, as did Bank of America, leaving the Tallinn operation without access to dollars. Danske Bank disbanded the branch’s foreign banking division.

Danske’s reckoning

The first public revelations about money laundering clients in Estonia appeared in 2017 news reports published by ICIJ media partners Berlingske and OCCRP. Afterward, Danske Bank’s head office in Copenhagen hired Danish law firm Bruun & Hjejle to investigate.

In 2018, the bank published Bruun & Hjejle’s scathing report, which effectively confirmed that, over nine years, Rehe’s unit had quietly turned into a money laundering machine, helping shadowy figures from Russia, Eastern Europe and Central Asia wash as much as $230 billion in dirty money. The 87-page report offered a detailed account of the many obvious signs of money laundering there for anyone in a position of responsibility willing to see.

The whistleblower Wilkinson testified before the Danish and European parliaments, and the Danske Estonia scandal became a major news story across Europe and around the world.

Thomas Borgen, Danske Bank’s chief executive, resigned immediately after the Bruun & Hjejle report was released in September 2018. In May of last year, Borgen’s lawyers confirmed to Danish media that investigators had searched the former CEO’s house and that he had been charged, though they did not specify the offense.

Estonian police records show that Beta Consult, the U.K. LLP and LP wholesale operation, was secretly run in part by Danske Estonia’s star banker Juri Kidjajev and account managers in his foreign banking division, including Anna Kurilenko.

Kurilenko, who had previously worked at a Tallinn formation agency, was arrested in 2018 as part of Estonian authorities’ probe of the branch. According to leaked minutes of a police interview, Kurilenko denied knowing much about Beta Consult.

“The company was involved in setting up and servicing legal entities; it provided legal services,” she said. “I don’t remember the name of the manager or the actual owner. I don’t remember how this company came into my portfolio.”

She also said she didn’t know how cash deposits equivalent to almost $385,000 had landed in her bank accounts since 2011.

“Because it’s such a long period, I’m not clear in my head, but it certainly doesn’t come from crime,” she told police, according to the minutes. “This is family money.”

According to the leaked Danske Estonia records, Beta Consult’s true owner was supposed to be Yevgen Varnakov, a businessman based in Ukraine. But when a reporter in Ukraine from ICIJ’s partner, OCCRP, tracked him down by phone, he said he had never heard of Beta Consult. “It’s the first time I heard about such companies,” he said.

“ I didn’t have any connection to the operations [of Beta Consult] and I didn’t receive any benefits from it,” he added in a further exchange by text message. “How much clearer can I be?”

For her part, Kurilenko told police that she couldn’t remember if she knew Varnakov.

Police files show that in 2018 authorities believed that Kurilenko, Agnevštšikov Juri Kidjajev and at least nine other former Danske Estonia staff members conspired to hide $786,184,653 in suspicious transactions, $284,201,266 of which amounted to laundering. Since then, their investigations have widened and investigators are looking into up to $2 billion in suspected money laundering.

Contacted by ICIJ, the bankers declined to comment, while Anastassia Kidjajeva, who has not been named as a suspect, could not be reached.

The documents reveal that police in Tallinn found jewelry, cash, gold and cars linked to former Danske Estonia bankers and want to know how these items were paid for.

When police questioned Agnevštšikov, the account manager, about how he had bought a Range Rover Sport car, he said he had paid the equivalent of $57,000.

“Payment was made in cash,” he said, according to a translation of a leaked notes of his response. “The money came from Russia. But I do not know whether the people from whom I received this money want me to publish their names in this procedure. This does not apply to Danske’s issues. Before publishing their names, I need to talk to them personally.”

In some cases, the bankers admitted that they had received loans from the bank’s clients to buy properties or start businesses.

Last year, Latvian police, in cooperation with Estonian counterparts, opened a money laundering probe into $2.1 million in a bank account belonging to a U.K.-registered LP, Medford Impacts, publicly owned by Mihhail Murnikov, a former Danske Estonia account manager. Estonian prosecutors named Murnikov as a suspect in their inquiries a year earlier.

Murnikov declined to speak to ICIJ, but in an interview last year with Bloomberg News, he said: “The whole [Danske Estonia foreign banking] business was built on one principle: Everyone was making money on cross-border transactions because non-residents had to pay $90 per transaction.” He said each transaction normally costs the bank $1.

“I had a clear plan,” explained Murnikov, who oversaw 300 customer accounts. He needed to “make 40,000 transactions a year so I could get a bonus.” The only performance measure used to determine his bonus was the number of transactions he handled, he said, adding: “You were directly motivated by getting as many clients as possible. Everything else wasn’t important.”

Big banks’ indispensable money laundering role

An amount equivalent to 2.7% of global economic output is laundered annually through the international financial system, according to a United Nations estimate based on 2009 data. Today, that amounts to a staggering $2.4 trillion. Most of it involves cross-border transfers, disguised as legitimate international business transactions and conducted in U.S. dollars.

Local banks, such as Danske Estonia, can’t move money around the world without an intermediary. For dollar transactions, they need the services of a bank with access to the U.S. Federal Reserve System. These so-called correspondent banks, usually global giants, allow senders and receivers with accounts at smaller overseas banks to send money without having to open an account in the United States.

The system gives correspondent banks, which can serve thousands of foreign “respondent” banks, a privileged vantage point over global money movements. It also gives them frontline responsibility for stopping money laundering.

Fourteen of the world’s largest banks spent $2.6 billion on compliance efforts in 2018, according to a survey done for the Bank Policy Institute, a U.S. industry body.

The global banks employ thousands of staff to review transaction alerts generated by computer algorithms, each of which could warrant a suspicious activity report. One senior compliance executive estimated that the average SAR costs a bank $10,000, or “about the same as a small car,” to produce.

But ICIJ’s investigation found that anyone with access to confidential reporting on bank transactions — which would include bank compliance officers — could figure out that Companies House records are littered with fake filings by U.K. LLPs. (LPs are not required to file financial reports.)

ICIJ’s analysis showed huge discrepancies between enormous amounts of money flowing through the bank accounts of U.K. LLPs and LPs, on the one hand, and the minimal income and expenditure recorded in their official financial statements, on the other.

The Belgian dentist and the $4 billion mystery

For years, Deutsche Bank handled the transactions of U.K. LLPs and LPs that later turned out to be, by the bank’s own admission, money laundering vehicles.

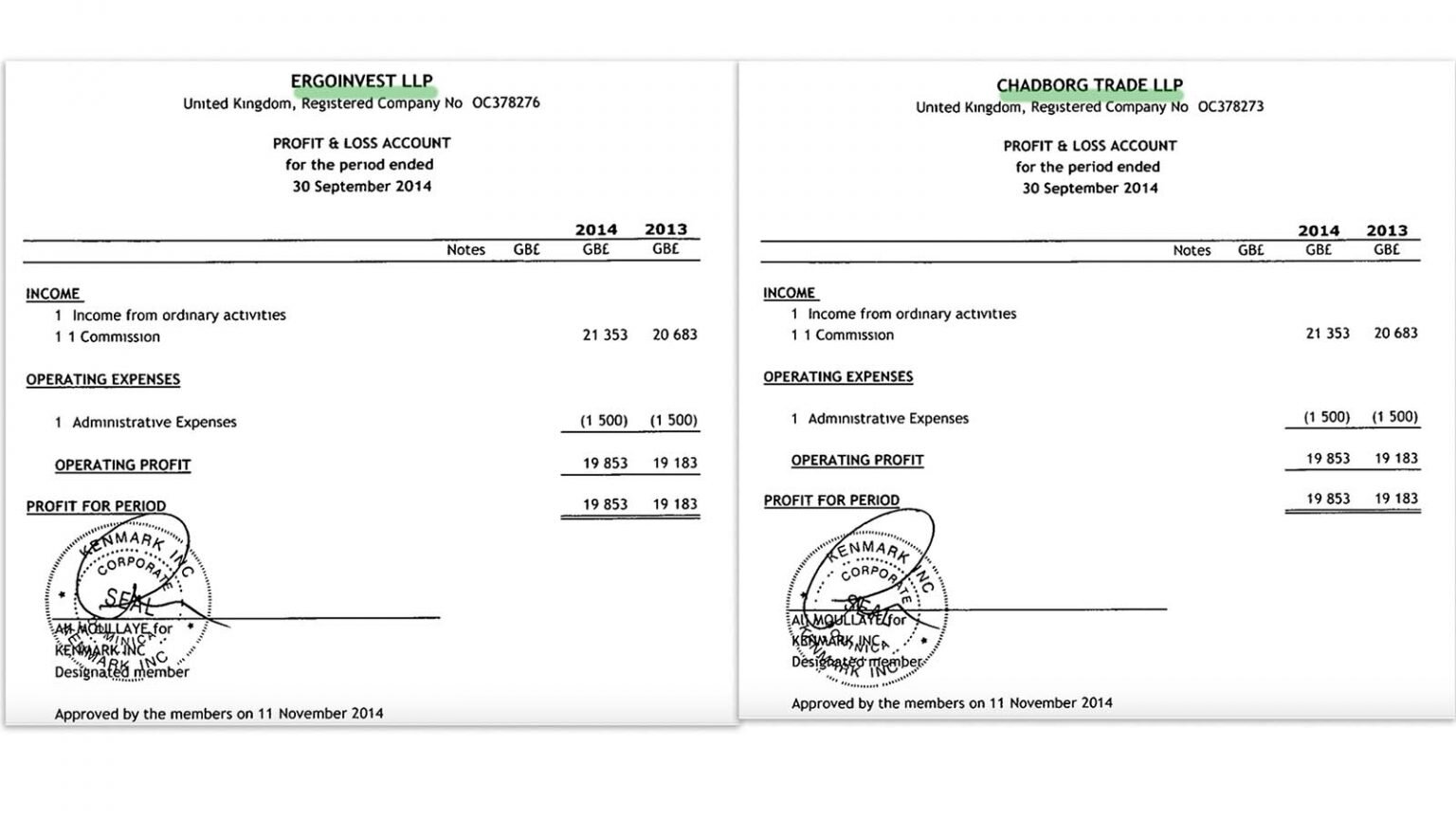

In early 2015, Deutsche discovered that its stock-trading operations in London and Moscow were part of a laundering scheme that made use of a practice known as “mirror trading” and involved equity clients that included two U.K. LLPs, Ergoinvest and Chadborg Trade.

The FinCEN Files show that in a 2015 SAR, the bank admitted that its New York branch, over the previous three years, had helped process payments of $2.6 billion to Ergoinvest and $700 million to Chadborg Trade.

Not mentioned in the Deutsche Bank report: the same two U.K. LLPs had each declared annual income of no more than $35,000 in 2013, 2014 and 2015 financial statements sent to Companies House.

The statements for both companies are not only false but also essentially identical — another sign of possible fraudulence.

Statements of declared income for Ergoinvest and Chadbourg Trade.

The statements for both companies were signed with a squiggle including a circle and two lines over the printed name of Ali Moulaye, a dentist who lives in Belgium.

Moulaye’s signature appears on at least one year’s financial statements for 385 U.K. LLPs named in the FinCEN Files, making him by far the most prolific straw man in ICIJ’s analysis.

And for nine of these LLPs, the FinCEN Files show a total of $4.1 billion landing in their bank accounts between 2012 and 2015. But these same companies said in financial statements filed with Companies House — and signed by Moulaye — that they had combined revenue of less than $500,000 during the corresponding period, ICIJ found.

Moulaye has never been charged with wrongdoing.

A reporter from ICIJ’s Belgian partner Knack tracked Moulaye down to his modest home, a former cafe facing onto a busy arterial road on the outskirts of Brussels where he lives with his Latvian wife and family. Moulaye opened the door in bare feet, wearing jogging pants.

Shown some of the false financial statements bearing his signature and asked for an explanation, he said: “Very simple. I know nothing about it… My signature can be falsified by anybody. That is not difficult. It’s a circle and two lines … I know nothing about it. I am a dentist. I don’t need to do such things.”

Asked about the missing billions flowing into LLP bank accounts, he added: “Then I should be a millionaire… [but] we have nothing. Not even a car. Then I shouldn’t be here. Then I should be elsewhere, with a car, with my own [house]. And you can check my money, my income, everything.”

Moulaye confirmed that he had lived in Latvia until 2014 and that the signature on LLP financial statements resembled his own. But he added: “I only have two old bicycles that I bought for 200 [euro], this house we bought with the loan… That’s it… Frankly speaking, I don’t even know what an LLP is.”

Missing the mirror trades

In a 2017 money laundering settlement, New York state’s Department of Financial Services found that a European bank approached Deutsche Bank with concerns about large payments involving a certain stock-trading company as early as 2014, but that a senior compliance officer had failed to investigate. The officer later told the New York regulators that he had had “too many jobs,” and that he “had to deal with many things, and had to prioritize.” ICIJ has learned that the trading company was Ergoinvest.

A separate investigation into the mirror trading scandal, conducted for Deutsche Bank by Deloitte, found that the bank’s automated anti-money-laundering systems flagged Ergoinvest 12 times between July 2013 to January 2015. Each time, however, the bank’s compliance staff reviewed the payments to the U.K. LLP and decided against even submitting a suspicious activity report, according to a draft of Deloitte’s confidential report, obtained by ICIJ’s German partner Süddeutsche Zeitung.

New York regulators fined Deutsche Bank $425 million in the 2017 case, saying it “missed numerous opportunities to detect, investigate and stop” shell companies at the core of the mirror trading scheme.

In July of this year, New York fined Deutsche Bank an additional $150 million for anti-money-laundering failures, including the bank’s role in illicit money flows through Danske Estonia accounts owned by U.K. LLPs and LPs.

New York regulators noted that Deutsche Bank over eight years had itself identified 340 suspicious transactions involving Danske Bank clients. The state found that Deutsche helped move at least $150 billion for the customers of Danske Estonia, and that the ultimate owners of the accounts were people not from Estonia but from Russia and other former Soviet states.

Deutsche Bank declined to answer specific questions about its processing of U.S. dollar transactions for Ergoinvest and Chadborg Trade. In a general statement, it said: “We ourselves reported [these money laundering concerns] to our regulators and authorities… We acknowledged past weaknesses in our control environment, we apologized for this and accepted our respective fines. Most importantly: we learnt from our mistakes… We are a different bank now.”

For banks, ignorance is profit

After helping to blow open the Danske Estonia scandal, Wilkinson, the currency and bond trader, would present the case as an indictment of the entire multibillion-dollar anti-money-laundering compliance system.

In 2018 testimony before the European Parliament, Wilkinson denounced lax U.K. regulation. “Clearly the worst of all is the United Kingdom,” he said. “I think one has to be slightly polite when one comes to an institution like this, but one doesn’t have to be polite about one’s own country. The role of the U.K. is an absolute disgrace. Limited liability partnerships and Scottish liability partnerships have been abused for absolutely years.”

But he also said U.S.-based correspondent banks shouldered a large portion of the blame for helping Danske Estonia become a money-laundering machine.

“It’s important to stress these correspondent banks in the United States,” he told the parliament. “In my estimate, 80 to 90 percent of the money that went through Danske Bank ended up in dollars, leaving through U.S. correspondent banks into the financial system.”

He added: “The banks in the U.S., including the U.S. subsidiary of a European bank, were basically the last check. Once the money got through them, it was out, clean and into the global financial system.”

The European bank he was referring to was Deutsche Bank.

Wilkinson declined to comment to ICIJ.

Martin Woods, another whistleblower and a former compliance officer at the U.K. branch of Wachovia Bank, can appreciate what Wilkinson went through. In 2008, he helped check a few U.K. companies as a favor to colleagues. Very quickly, he, too, discovered shell entities, banking in Latvia, whose transactions didn’t match records at Companies House. He even wrote a suspicious activity report about it.

In an interview with ICIJ, Woods, who earlier in his career spent 18 years as a police officer, said resistance from Wachovia colleagues forced him to blow the whistle and eventually leave the bank. U.S. authorities later fined Wachovia, now part of Wells Fargo, in connection with separate money laundering allegations brought by Woods and others.

“The people who [are supposed to] actually investigate money laundering [at correspondent banks] deliberately seek not to find out information that may give them a problem with maintaining relationships,” Woods said. “To me, it was a deliberate course of action.”

He added: “Knowledge isn’t power in this business. Knowledge is contamination, so, you make sure you don’t get contaminated.”

“There is no possibility that we can be 100 percent sure what this company is actually doing.”

After Danske Estonia, forming UK shell companies

After Juri Kidjajev’s foreign banking division was shuttered in 2015, former staffers scattered to new jobs. Some became consultants working with agencies forming U.K. LLPs and LPs.

Three former account managers — Murnikov, Agnevštšikov and Marko Teder — set up a consulting firm, NRD Advisory.

The firm courted customers outside the European Union, helping them to set up companies “in various jurisdictions” and open bank accounts in Baltic countries, according to an archived version of NRD’s now-defunct website.

The three principals are now among those named as suspects in the Danske Estonia case. Each declined to respond to ICIJ questions. NRD has been shuttered.

Erik Lidmets, another former member of Danske Estonia’s foreign banking division, left the bank earlier than others after he was sacked in 2010 for misconduct. He went on to run a formation agency, Amicus Consilio. According to archival records of its now inoperative website, it helped clients set up offshore companies as well as “certain forms of companies in onshore jurisdictions.”

Lidmets has also been named as a suspect in the Danske Estonia case being pursued by Estonian prosecutors. He, too, declined to respond to ICIJ questions.

According to Companies House paperwork, the U.K. parent of Amicus Consilio was set up by Ghassan Hoteit, a junior book-keeper who, as part of a side business, started the U.K. arm of the formation agency from his flat in north London.

In interviews with ICIJ, Hoteit said that a Latvian lawyer hired him as a straw man to act as a director and a shareholder of Amicus Consilio and many other firms — mostly LLPs and LPs. Hoteit said he was paid about $1,300 a month. He said he had never heard of Lidmets.

He said the lawyer had assured him that appropriate background checks had been made on the companies involved.

“And after a while, I stopped my involvement” with the shell companies, Hoteit said. “I just didn’t — to be honest, I started learning more about directors’ responsibilities, and I decided this was not something for me.”

He added, “Back then I was 24, 25, and obviously I came to London when I was young and no one told me about these things.”

Hoteit expressed regret over his involvement. “Now I’m at a stage in my career where I look back at that, and I’m embarrassed,” he said. “I was really naive. And I know naivety is not an excuse. It is what it is. It’s a young person’s mistake, I guess.”

An analysis of leaked Danske Estonia records show 109 companies set up by Hoteit and associated companies went on to open a bank account at Danske Estonia, typically within three months; 40 of them were registered to his home address.

After Hoteit stopped acting as a straw man, most of the companies he had set up, including Amicus Consilio, had a change of address, moving from his north London flat to the U.K. home of beautician and house cleaner Dace Streipa.

As for Aivar Rehe, the banker never recovered from the Danske Estonia scandal.

He moved to another bank for a bit, but was soon out of work. When prosecutors held a press conference at the end of 2018, they named many of Rehe’s former staff as criminal suspects, but added that — despite demands from some anti-corruption activists — Rehe himself was not, at that moment, among them. “I stress, at the moment,” one prosecutor said.

Nine months later, they found his body.

In a statement to ICIJ and its partners, police this month said: “Aivar Rehe was questioned as a witness but not as a suspect. We can say that so far we haven’t seen anything in the criminal investigation data that would lead us to believe that Rehe had been engaged in money laundering.”