How we Followed the Garbage

Maja Čakarić, Matej Zwitter

—

We tried to hide the tracking devices in the waste items so well that collection centre workers wouldn’t notice them. We managed to achieve this with some ingenuity but the tracking process did not turn out entirely according to our expectations.

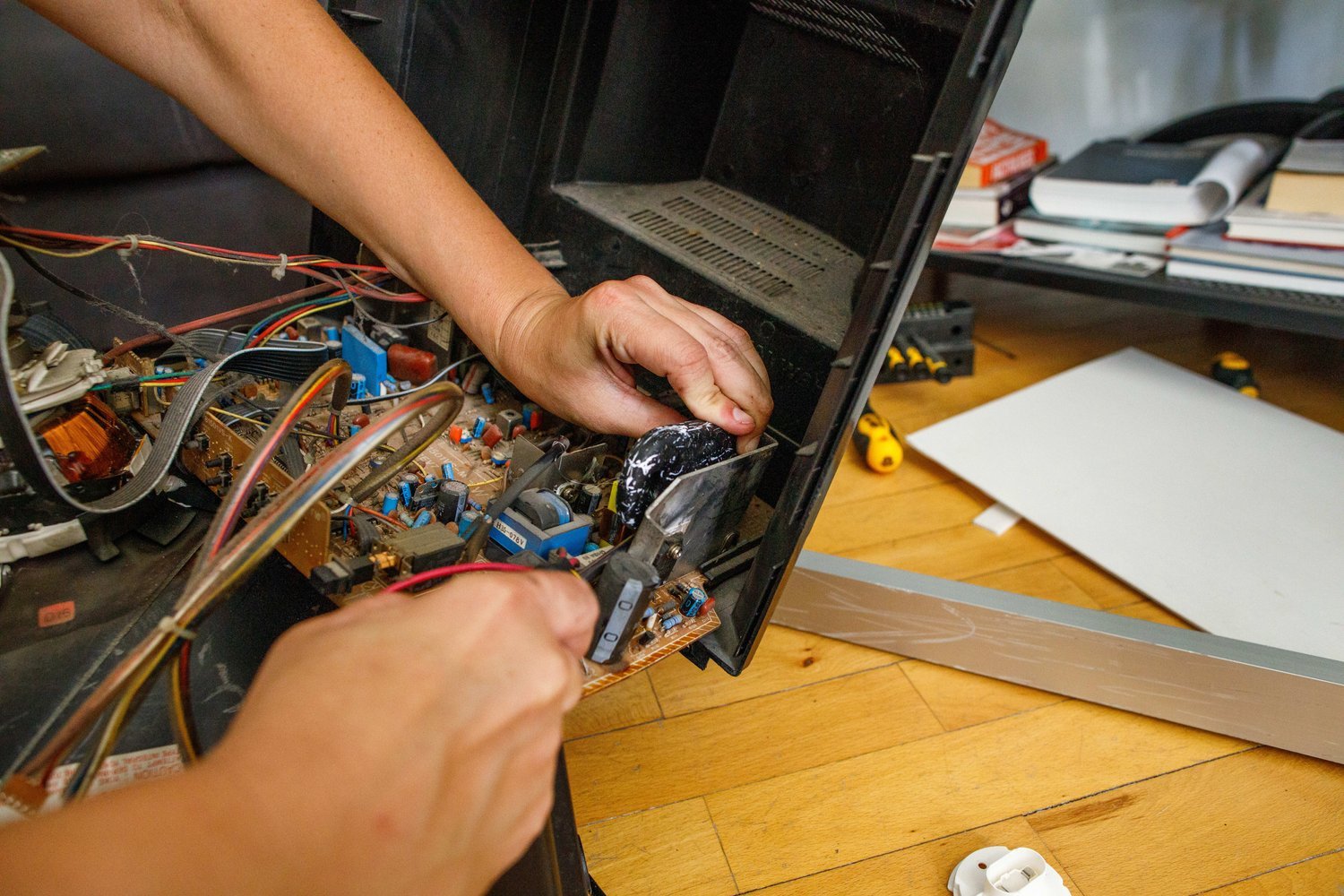

We collected the waste, processed it last summer and prepared it for the trip with a tracker. In the photo is Oštro’s journalist Matej Zwitter. Photo: Matej Povše

Follow the Garbage project is supported by Pulitzer Center

“They found the tracker,” Oštro’s reporter notified her colleagues after her talk with representatives of Humana, an organization that collects used clothing and textiles. In mid-January their warehouse workers found a tracking device in the pocket of a pair of torn jeans. It had been sewn into the trousers under the auspices of Oštro’s Follow the Garbage project.

In June and October last year, we attached, glued or sewn on tracking devices on 30 waste items, so that they would report their geolocation through the trackers’ mobile or web application.

We wanted to verify if the waste ended up in suitable processing plants. We threw one of the items into an appropriate bin for packaging outside one of the gas stations. It later got mixed with residual waste. Eventually, it ended up in the correct facility but this was because the garbage processing company sorted the waste before treatment.

The Follow the Garbage project flirts with similar past journalistic and academic investigations across the globe. In 2009, researchers from MIT in Massachusetts attached tracking devices to over two thousand waste items to investigate Seattle’s waste management system.

Five years later, researchers of the Canada-based Basel Action Network (BAN) that advocates for environmental justice monitored the paths of 43 used-up electronic devices to find that four of them were most probably illegally exported.

Journalists from the Finnish media YLE monitored the path of used clothing, as did journalists from the Swedish television SVT and the Lithuanian investigative journalism outlet Siena last year. They discovered organized theft of clothing donated to charities.

While we researched previous projects and data on waste management in Slovenia, we also had to choose a suitable tracking device; durable battery and a convenient size being of primary importance.

Following recommendations by colleagues from other investigative projects, we finally opted for a device by the Finnish manufacturer Yepzon. Its batteries are durable enough to last up to six months with conservative settings, and small enough to be hidden in communal waste items.

To extend the battery’s life we had to sacrifice some geolocation precision. According to the manufacturer's recommendation, we set up the devices so that they determined their location by using the less precise mobile data instead of satellite location systems, such as GPS. Getting a precise GPS location from the device drains its battery much faster, so we only asked for it when we detected that an item had moved to determine its exact location.

We collected the waste in the Oštro’s office, where the sculptor Neža and journalists prepared it for the trip with a tracker. Video: Matej Povše

Silence of the trackers

When choosing the waste items to equip with trackers, we took into account how common they are as well as their environmental impact, based on a review of reports on waste management. Our goal was to test the management of a diverse range of waste types thereby imitating the behaviour of citizens who sometimes respect the rules on waste disposal and sometimes not. We were also interested in the trajectory of less ordinary waste types that citizens bring to waste collection centres.

On a sunny summer day we collected all the waste items in Oštro’s office where Neža, a local sculptor, helped prepare them for their respective journeys with tracking devices in tow. She glued, tore and coloured waste to camouflage the bright white trackers, and Oštro’s journalists helped her however they could.

We cut up plastic bottles, disassembled the TV set, computer and vacuum cleaner. With clothing, we had to be more imaginative to ensure that the sewn-in trackers would not be immediately noticeable to sight or touch. We found a coat with padded shoulders in a second-hand clothing store. We filled a broken backpack’s pocket with foam in which we inserted the tracking device and sowed it up.

We overestimated our ingenuity with the aluminum tube. We first broke and dented it so that it looked useless, and inserted the tracker. We were about to send it on its way when we realised that the device was either too tightly squeezed within the tube or that the device’s signal could not penetrate the aluminum. Therefore, we probed the tracking device back out from the tube and attached it to another waste item.

The pieces of asbestos roofing constituted a special challenge given that the material can be very harmful for health. During a walk along the Sava river we found a pile of illegally dumped asbestos roof panels along the footpath. For health reasons, we didn't want to deal with them in the office.

A reporter put on protective coveralls, boots and a breathing mask, then attached the tracking devices on the underside of the plaques and covered them with some artificial moss to make them look as inconspicuous as possible. The roofing was then wrapped in protective wrap in accordance with the law and prepared for transport to a collection centre.

We disposed of other waste items in waste bins in front of homes, took them to collection centres and on a trip around the country to avoid overly centralizing the investigation to the country’s capital. We managed to cover all statistical regions.

Photo Gallery

Authors: Matej Povše, Oštro

Waiting Game

We set the tracking devices to report their approximate geolocation every six hours after every move. If the item was still, they pinged their location once per day. All moves were registered in a growing database.

Just a few days after we first disposed of the waste, we were pleased to register the first move: the plastic bottle of yoghurt was transported from Petrol’s gas station in Kozina to the Sežana waste management centre, some 15 kilometers away.

But our enthusiasm was short-lived. Several devices stopped broadcasting their location, although they still had a sufficiently full battery at the time of the last contact. Yepzone’s analysts helped us understand the “disappeared” trackers and establish two hypotheses: either the devices were squished by the hydraulic mechanism in the garbage truck or they had been buried under the trash in metal containers, unsuccessfully trying to establish a connection for so long that their batteries ran out.

After the first month, we lost contact with over half of the initial batch of 20 tracking devices, so we decided to launch a new batch of ten on their way. This time, however, we used more durable tracking devices that were designated to monitor trucks and construction machines. These devices are much larger and heavier, so we had to carefully choose which waste item we will hide them in.

At the time of publication, four tracking devices were still transmitting their position – in the electronic candle, car tyre, vacuum cleaner and jeans. That said, the latter is no longer hidden in the jeans because Humana found it and removed it after Oštro’s media inquiry that included the disclosure of the existence of waste trackers.

A few days before publication, the tracking device hidden in a broken backpack also stopped emitting its signal. Its last registered location was the container terminal of the port in Rijeka, Croatia. We shall never know which country, most likely in the less-developed south, it finally ended up in.

Do you know of a case of unsuitable waste management? Let us know about it via e-mail: contact@ostro.si. We shall check upon the relevant information and, in case of suspected irregularities, also investigate them.