Tyre removed, illegal dumping site cleaned

Matej Zwitter, Maja Čakarić, Klara Škrinjar

—

Oštro’s reporters disposed of various waste items in containers and collection centres across the country. All items were equipped with hidden tracking devices that were emitting their geolocation data. What follows below are some of the more interesting findings.

Oštro discarded the used car tyre at an existing illegal dumping site then informed the environmental inspectorate about the pile of waste. Photo: Matej Povše

Follow the Garbage project is supported by Pulitzer Center.

Between 2011 and 2020, the quantity of used car tyres collected in Slovenia has increased by one third, according to the Slovenian Environment Agency’s data.

Last year, two used tyres were thrown away by Oštro’s journalists. One was disposed of at an existing illegal dumping site because reporters wanted to test the environmental inspectors’ responsiveness to the public’s complaints.

Reporters located a small pile of construction waste, tyres and a toilet seat on a road connecting Črnuče, a neighbourhood in the capital of Ljubljana, to the highway going north.

Making a citizen’s complaint, Oštro’s collaborator notified the state environmental inspectorate of the illegal pile of waste. Because it appeared that the pile wasn’t left behind by a company but more probably an individual, the state inspectorate redirected her to the municipal inspectorate in Ljubljana. The local government body asked her to submit photographs of the site and its accurate location.

Twelve days later, they notified her that the inspectors had examined the location and issued a decree to the public company Vo-Ka Snaga to remove the pile of waste.

Another two weeks later, the tracking device indeed emitted a signal when it moved towards Ljubljansko barje, a marsh region on the outskirts of town, but Oštro shortly lost connection. From the geolocation data, journalists concluded that the tyre most probably arrived at the waste collection centre in Barje. Its project manager Jože Gregorič told Oštro that used tyres are stored until Get inženiring company, a waste buyer, picks it up.

Last autumn, Oštro took the second tyre directly to a Get inženiring facility in Kresnice near Litija municipality. It remained there but by the time of publication the signal was lost.

The company’s CEO Roman Koprivnikar said that the tyre, depending on its state, could either be processed on the day of collection, or it can wait in the collection centre for up to six months. If it is still usable enough, it is separated from the others and exported, for the most part to Africa and Latin America. The rest are handed over to the transferee, the Slopak company, which then transports them to the incineration unit of the cement factory Salonit Anhovo, to cement producers abroad or to the Croatian company Gumiimpex GRP for recycling.

According to the Ministry of environment and spatial planning’s data, more than 21,800 tons of used tyres were processed in 2020. Most of that, 65%, was used as fuel in cement plants, while the rest was sent to be recycled. Almost the whole bulk was recycled abroad.

Because of the environmental threat of burning tyres, Slovenia had already been on the radar of the Court of the European Union. Namely, the state failed to resolve the issue of environmental pollution after two fires broke out in the used tyres’ landfill in Lovrenc on Dravsko polje in 2008.

The area’s restoration at a cost of nine million euros was the responsibility of the Maribor-based company Surovina. It had finished restoring the space at the end of last summer, 13 years after the fire. The company had to remove 68 thousand used tyres and other illegally discarded waste.

An old television set was equipped with a tracking device and disposed of on 1 July at the collection centre of the company Surovina in Žalec. Photo: Matej Povše

Dismantling electronic waste

According to the environmental agency's data, in 2020 waste collectors collected a little more than 14,400 tons of electric and electronic equipment. By weight, large appliances, such as dishwashers and washing machines, represented the largest share followed by small appliances, such as vacuum cleaners and microwaves, and larger devices, such as television sets and computer monitors.

Among them was an old TV set that Oštro equipped with a tracking device and left it at a Surovina collection centre in Žalec. Less than two weeks later, the tracker reported a new location at Surovina’s unit in Maribor which is authorised to process several types of waste, among them televisions.

The company explained that electronic waste from all their collection centres is gathered in their Maribor unit. There, the employees disassemble electronic waste and then send the suitable parts to their contract partners for further processing.

Oštro also disposed of an old vacuum cleaner at the TSD company in Maribor where they collect and purchase discarded raw materials. Seven months later the vacuum cleaner is still there. Jani Goričanec from TSD told Oštro that they have not yet decided on whether it was suitable for reuse or not.

TSD is a partner of the Spodbujamo e-krožno (We Promote e-Circular) project where workers at collaborating organizations divide still usable electronic devices from the rest. Items, such as Oštro’s vacuum cleaner, are thoroughly inspected and then sold. Goričanec said they had to put the project on hold due to human resources issues, thus, waste items, including the vacuum cleaner, are still waiting to be processed.

Many children’s toys contain electronic parts, as did Oštro’s teddy-bear that used to »speak« and had a speaker inside. We made the teddy-bear uglier, so that it would not end up among toys, and then took it to the Postojna collection centre in September. By the end of the year, it was moved to the Mala Mežakla centre for communal waste treatment in Jesenice.

Publikus, the company managing the collection centre in Postojna and their subsidiary Mala Mežakla, warned Oštro that the teddy-bear was wrongly discarded among mixed communal waste because it had electronic parts. It should have been thrown away as electronic equipment waste.

At the Mala Mežakla centre, mixed communal waste is first sorted by size. Metals are removed from items larger than eight centimetres, such as the teddy-bear, and the rest is transferred to other companies for incineration.

The MPI Reciklaža daily collects and processes approximately 165 tons of batteries from Slovenia and abroad. Photo: Matej Povše

New lead bars from batteries

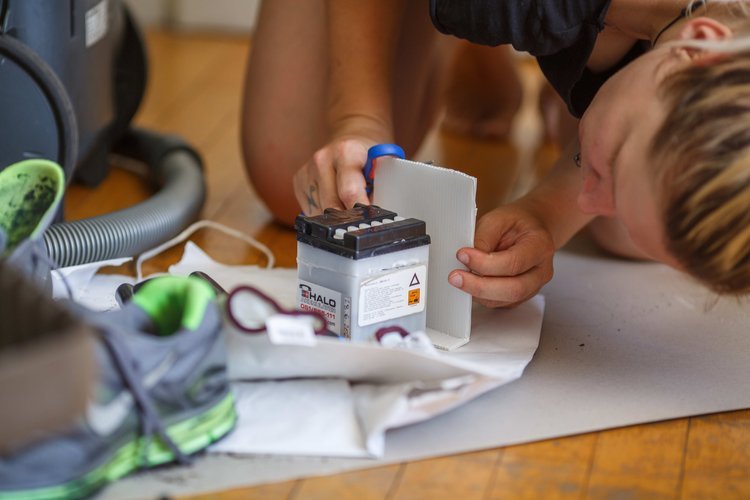

The motorcycle battery we had disposed of in the collection centre in Bukovžlak at the beginning of July was most probably recycled. It had been waiting in Bukovžlak for more than half a year, until it ended up in the facility of the MPI Reciklaža company in Črna na Koroškem in December. The company, whose primary business is recycling batteries and other lead waste, is a subsidiary of the battery producer TAB.

MPI Reciklaža collects and processes around 165 tons of batteries per day, Jure Popovič, a technologist at the company, told Oštro. First they extract the acid, then grind the batteries into smaller pieces, which are separated into lead and plastic parts. The lead is refined, cast into 50-kg bars and sold, while a part of the plastic is recycled and a part incinerated. The by-product of processing, slag, is deposed in the company’s landfill.

The candle was thrown away at the beginning of November at the Žale cemetery in Ljubljana. It later reached the Plastikon company in Jesenice, where it remained at the time of publication. Photo: Matej Povše

Candle headed for recycling

According to Arso’s data, a little over 1500 tons of used graveyard candles were collected in 2020. Most of the material in these candles, almost 84%, was recycled, while the rest was processed into fuel, incinerated or discarded in landfills.

Oštro attached tracking devices to two electronic candles. We threw the first one in the candle container at the Bohinjska Bistrica cemetery in July, but ten days later we lost contact with it.

The Bohinj municipality said that the container had only been emptied at the beginning of August, so the tracking device most probably lost its connection while it was still on the site. The candles from that cemetery are first taken to a collection centre and then handed over to the company Ekol.

The other candle was disposed of in a container at the Žale cemetery in Ljubljana at the beginning of November. Soon after it reached the facility of the Plastkom company in Jesenice, where it remained at the time of publication.

Plastkom first weighs the candles and separates paraffin wax candles from electronic lantern candles, the company told Oštro. The paraffin wax is melted and sold, while the housing of the candles is recycled.

The procedure for dismantling electronic candles is somewhat more time-consuming as they are first sorted by the material of the housing, after which the batteries are removed. Housings from PVC plastic are processed into granules, while those made of PET plastic are sent to incineration.

We attached two tracking devices on pieces of used asbestos roofing panels and took them to collection centres in Barje and Vrhnika. Photo: Matej Povše

‘Lost’ Asbestos Roofing

At the end of June we noticed an illegally dumped pile of old asbestos roofing near a footpath along the Sava river in Ljubljana. We chose it as suitable for the project.

A reporter put on protective clothing, boots and a mask and installed two tracking devices on parts of the roofing. The waste was then wrapped in plastic wrap as per the regulation on asbestos-containing waste and taken to collection centres in Barje and Vrhnika.

The tracking device disposed of in Vrhnika lost connection after a week. It is not clear why. The local public utility company told Oštro that they stack the roofing on palettes and wrap it in plastic, marked with the type of waste that it contains. Then it is handed over to the company Saubermacher that won the deal in a public tender.

Saubermacher stated that they transfer asbestos roofing to an “authorized company with all the required permits”. They did not reveal the name of that company.

Oštro managed to maintain the connection with the tracking device of asbestos roofing taken to Barje for slightly longer.

The public utility company Vo-Ka Snaga told Oštro that asbestos roofing is taken to a landfill a few hundred meters away two to three times a week. Such a small movement was not detected by our tracking device, thus, Oštro could not identify its final destination without a doubt.

Do you know of a case of unsuitable waste management? Let us know about it via e-mail: contact@ostro.si. We shall check upon the relevant information and, in case of suspected irregularities, also investigate them.